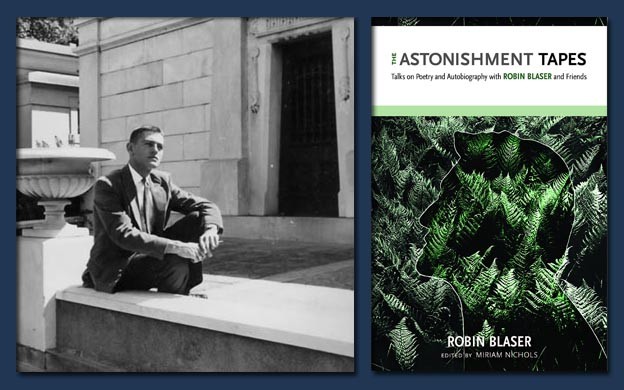

In his element

A review of 'The Astonishment Tapes'

Robin Blaser is in his element in these monologues in interview format — personable, pedagogic, and himself a “high-energy construct,” to not-quite-cite Charles Olson. By virtue of this book, the reader experiences Blaser as a unique force field of magnetic knowledge and charismatic charm. He is at home among the poets, themselves practitioners and friends, meeting in 1974 at someone’s house in Vancouver. The agenda is mixed: the taped sessions from which these talks are transcribed were apparently proposed by Warren Tallman to constitute or contribute to Blaser’s autobiographical memoir, and probably to dig into the complex nexus of a famous triad: Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, and Blaser. Their comradeship, quarrels, spites, and splits (among those involving other intimates) are one tale of the formation and impact of the “Berkeley” or “San Francisco Renaissance” in the New [North] American Poetry, a poetics and practice — with its accompanying lore — that energized these Canadian poets in distinctive ways.

As performer, talker, essayist, and poet, Blaser will not stay domesticated in literary history. The 1974 Vancouver tapes are therefore rangy, suggestive, allusive, and metamorphic. So the other part of the agenda for these meetings is both more buried and irruptive. Blaser is direct: “An autobiography is as much the intellectual loves as the personal loves.”[1] As if he were running a high-level seminar in the humanities and poesis, Blaser immerses his audience in poetics and poetry from Dante to Shelley, Mallarmé to seriality, touching on such poets as Olson, Pound, and Levertov, but also encompassing Western poetic and philosophic traditions. Blaser wants, needs, and desires to talk broadly, taking the defining interests of Duncan, Spicer, and himself as exemplary of the problematic of Western civilization after “religion” loses its binding force: what can the human be ontologically and epistemologically in the post-humanist period? And what, therefore, are the tasks of poetry? Indeed, Blaser’s Dantean framework became quite clear to me in reading this book — not sure why this book particularly, but there it is. In fact, Blaser is one of the striking users of Dante among contemporary poets, but unlike John Kinsella’s or James Merrill’s, his Dante is somehow distributed into and saturated within “Image-Nation,” the serial poem pulsing at irregular intervals through his collected poems, The Holy Forest.

No comments:

Post a Comment