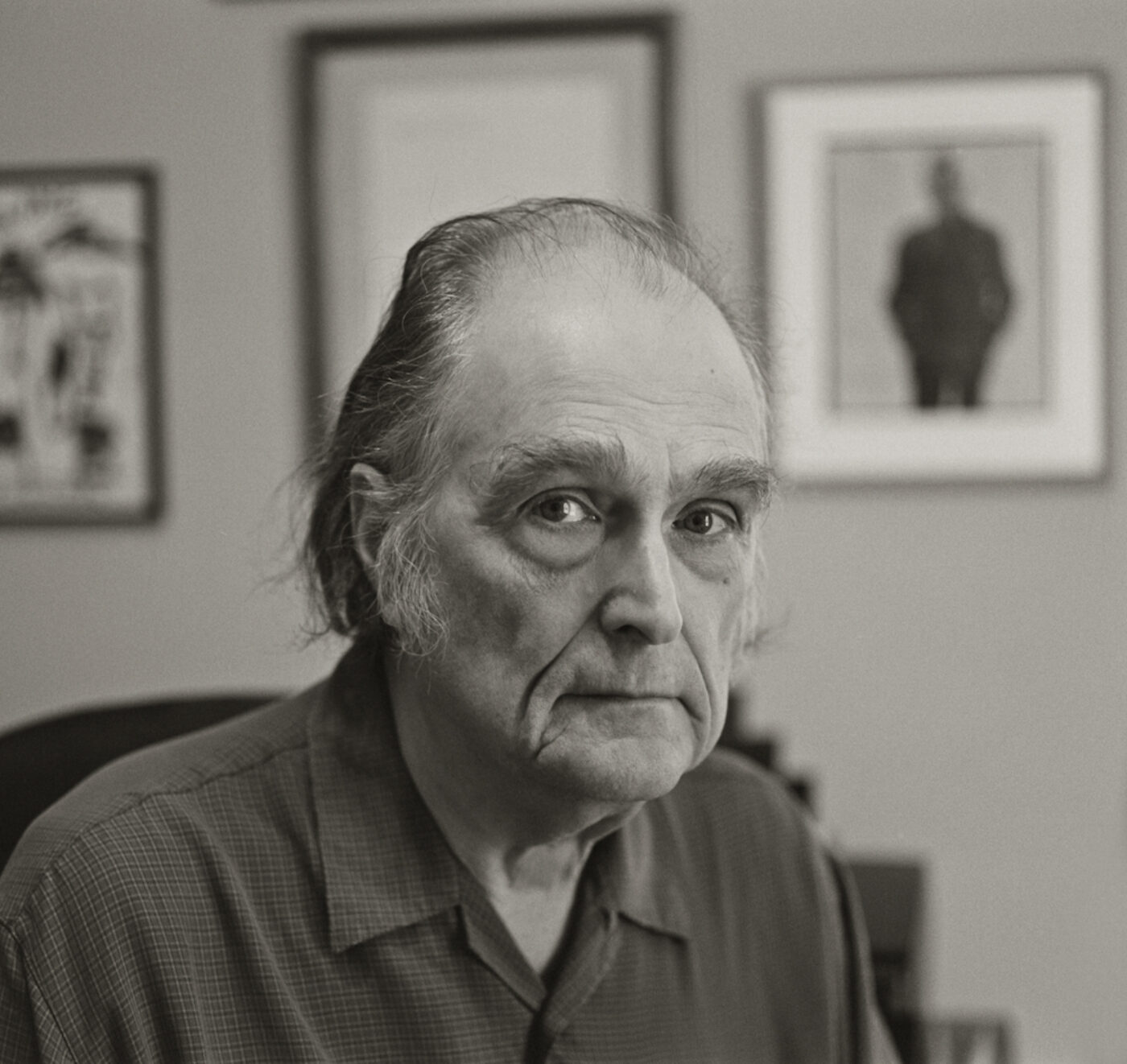

Photo of Clark Coolidge By John Sarsgard.

PMIn an interview with Tom Orange for Jacket you said, “you always have your basic language, or your subconscious choices, or whatever it is.” I’m interested in this idea of “basic language.” Does the process of retranslating compel you to bring in new language?

CCI’m basically using my memory of language—that may be one way of putting it—which would be what I remember from spoken language, and what I remember from the page. If I’m writing at a certain pace I can pick up things from all those areas and associate. I wrote a lot of these things without really realizing what I was writing. I was writing fast. I knew what the project was, of course, but I wasn’t trying to make it be something. I mean, it had to make itself something through me.

PM You’ve said that creating work can be like “feeling a shape.” Which I interpret as, finding a form and then working language into that form. Is that something you were doing with these?

CC It may have been Schoenberg who said “I sense the envelope of the piece”—I think he used the word envelope—“before I write any of the notes.” I can see, sort of dimly, this general, overall form. And then I use that. There’s some kind of—a manner of speech, I’d say—that Hanshan uses. A kind of first-person narration of memories, or events, or adventures. And I don’t think I could totally avoid that if I wanted to. It relates to the epigraph, where I talk about living on the green schist, which is the bedrock of the Taconic Range we were living on.

PM I was interested in that epigraph, partly because it gives us this geological vocabulary to run with. I know that’s very important to you. It made me think of a disagreement you once described with Aram Saroyan: his reading of your work as “a big cliff of rock.” And you said, “Geologists read the rocks.” I thought of the word schist in that context. It’s a word of differentiation.

CCIt ended up that I was a major in geology at Brown, two years before I realized, Hey, you know, you’re not going to do this. What you really want to do is run around the woods and find crystals.

PM I love thinking about these poems as the outcomes of a descriptive science of words. There’s so much careful attention paid to the properties of each word.

CC Yeah, that’s nice. As long as it carries me forward, and I’m not just stuck with some definition. Right? You wouldn’t want that.

PMLet me ask about the use of arrangement in these poems. These poems are roughly four-to-nine lines, and there’s a lot happening with enjambment. But there’s no extra space within the lines, something that you’ve worked with before.

CC By the time I was writing To The Cold Heart, I was more into phrases and sentences rather than just single words, although the single words are there. John Ashbery was interviewed, I think in the ’60s, or early ’70s, by Bill Berkson, who asked him a lot of questions about The Tennis Court Oath and that period of his writing. The main poem we were fascinated with was a numbered sequence of short poems called “Europe,” some of which are literally one word. John said, “I wanted that to be the whole experience. I wouldn’t reduce that word or associate it with anything else. I would just put it right in the middle of the page.” He said later he wanted to give that same feeling of an isolated object, a charge or whatever, to a phrase, maybe even a sentence or a paragraph. That’s something I’ve thought about, and I never associated with him, but there he is saying it in this suppressed interview that was never actually published. I guess I’m trying to say, that in terms of arrangement, I wanted to have that same emphasis on a phrase or a sentence or some longer linguistic figure. That was my argument with Aram. He would reduce everything down to one word. I would reduce it down to one word, and then accumulate other words around it.

PMThat’s an interesting way to think about the poetic phrase, a kind of accumulation.

CCBack then I wanted to put things together that didn’t normally go together syntactically. I was working with tape in the ’60s. I would put words on loops of tape. Put one word on one loop, and another word on another loop, and the loops are different lengths. Let’s say you had two words that normally go together, like “I see.” Play them at the same time and the gap between the words changes—they would be two separate words. Just two words going by each other at different speeds.

PM In the Orange interview you talk about how a project can “get ahead of you,” and compel you to “chase it down.” I think you said, “I’ve always been following something. If it stops pulling me then I will stop.”

CCThere have been times when I thought maybe I was finished. Something happened toward the end of the ’90s, just before I moved out here when I thought, You know, I’ve written an awful lot, and maybe I didn’t have to do this anymore. I mean, there’s a side of it that’s not entirely pleasant, you know? You’re pushed and pulled and you want to find what’s there. On the other hand, you get up every day and think, I’ve got to do this again? Then, within days of that feeling, I would find myself writing another line. I realized, like many of us have realized, that it’s not under our control. Evidently, this is what we’re supposed to do.

PM What are you following now?

CC Well, I’m trying to play the drums again. I had a couple of strokes a couple of years ago, and I lost function of most of my left side. My left hand and foot. I didn’t lose any speech, or brain function, but I couldn’t control my left side. I’ve gotten a lot of it back, but there still are things that aren’t automatic anymore. On the other hand, I’ve found it interesting that I’m forced to stop and look at these things that I would normally do, and think of doing other things. Maybe slower things, more simple phrases. Poetically—do you know Nathaniel Mackey’s work? Did you see that new box set that New Directions put out?

PMIt’s gorgeous.

CCThat’s almost one thousand pages of poetry. In one shot. It’s amazing. In that book there are two main poems that were happening in parallel, and he’s been writing them for twenty years. I’ve been doing something similar. I’ve realized, in the middle of all this writing, after twenty years, that it’s really all one work. I think there are about seventeen thousand pages or something like that. And I’m not exaggerating. In the last ten years it’s been mainly sonnets, which I don’t understand. I never had that much interest in sonnets, per se. I know I was really influenced by Ted Berrigan’s sonnets. A lot of us in that generation were. Even if we thought we came out of William Carlos Williams, it turned out it’s maybe so basic to the poetic effort that you can’t get away from it.

PMYou published some of your sonnets in 2013, right? With Fence Books.

.

Trying to get home, trying to get home

I pulled on the chin link until your coffin tipped.

Later, you came home. Welcome to your corner

above the books. Meanwhile I asked you to follow

me as far as I could go. You’re already farther

than that, thinning predators for history.

History being the first sign that we should

have ducked. Is changing the story the tiniest

bit really enough? Should we execute the principles,

or just the ones we wish were dead? I’ve changed

the story a little bit, though I’m not sure anyone noticed.

A little Cuban-sounding brass now from

Haitian players, mid-tempo, humid horns.

In a comment to my replies to Jonathan Mayhew’s questions the other day, Pris Campbell asked a pointed question:

After your mention of Clark Coolidge as one poet you found initially difficult to understand, I read some of his work on the Internet. This is from the beginning of The Maintains, and I hope it's okay copyright-wise to quote just the first few lines out of about a 3-4 page poem...

such like such as

of a whist

a bound

dull

the mid eft

lulu

the mode

own of own off

partly of such tin of such

the moo

which which

lably laugh

No comments:

Post a Comment