- Wanderer, your footprints are

the path, and nothing else;

wanderer, there is no path,

the path is made by walking.

Walking makes the path,

and on glancing back

one sees the path

that must never be trod again.

Wanderer, there is no path—

Just your wake in the sea.- "Proverbios y cantares XXIX" [Proverbs and Songs 29], Campos de Castilla (1912); trans. Betty Jean Craige in Selected Poems of Antonio Machado (Louisiana State University Press, 1979)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2021

(672)

-

▼

November

(163)

- Weldon Kees

- Elizabeth Bishop

- Weldon Kees

- Weldon Kees

- Srikanth Reddy

- Eugenio Montale

- Franz Wright

- Jeffrey Eugenides

- Franz Wright

- Antonio Machado

- Charles Olson

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Primo Levi

- Franz Wright

- William Burroughs by Andrew O'Hagan

- Franz Wright

- Gerard Manley Hopkins

- Fernando Pessoa

- David Meltzer (young) ala Jerome Rothenberg

- Philip Whalen

- Philip Lamantia

- Rae Armantrout

- Larry Eigner per Robert Grenier? or?

- Robert Grenier

- Robert Grenier

- Eugene Guillevec

- Lise Deharme

- Paul Eluard

- Andre Breton

- Andre Breton

- Fady Joudah

- Tristan Tzara

- Jack Spicer

- Jack Spicer

- Jack Spicer

- Jack Spicer

- August Sander

- Jack Spicer

- Fady. Joudah

- Robin Blaser

- Federico Garcia Lorca

- Gabriel Ojeda-Sagué

- W. H. Auden

- Christopher Isherwood

- Isamu Noguchi

- Louis MacNeice

- Sylvia Plath

- Dodie Bellamy

- Dodie Bellamy

- William Butler Yeats

- Samuel Beckett

- Stanley Kunitz

- Stanley Kunitz

- Countee Cullen

- Robert Hayden

- JAMES WRIGHT

- Cesar Vallejo

- Cesar Vallejo

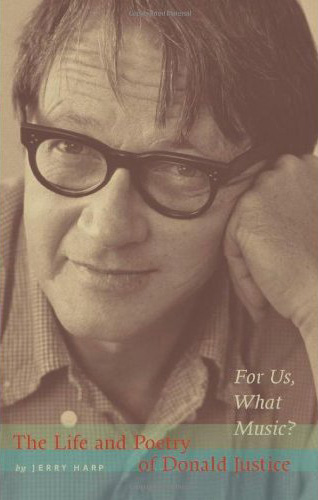

- Cesar Vallejo channeled by Donald Justice

- Donald Justice

- Ron Padgett to Joseph Ceravolo

- Joseph Ceravolo on James Schuyler

- Bill Berkson & Frank O'Hara

- Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman

- Bob Perelman

- Francis Ponge

- Clark Coolidge

- Hoa Nguyễn

- Mary Ruefle

- Mary Ruefle

- Agnes Martin

- Jack Gilbert

- Jack Gilbert

- Danlil Kharms

- Danlil Kharms

- Jack Gilbert

- Vladimir Mayakovsky

- Joseph Brodsky

- Nikolay Gumilev

- Bernadette Mayer

- Clark Coolidge

- Gertrude Stein

- Clark Coolidge per Ron Silliman

- Joan Retallack

- Joan Retallack

- Joan Retallack

- Pee Wee Herman

- Mark Strand on Donald Justice

- Mark Strand

- Donald Justice

- Donald Justice

- Paul Blackburn

- Paul Blackburn

- Agha Shahid Ali

- William Carlos Williams

- W.S. Merwin

- W. S. Merwin

- Wallace Stevensl

- Marianne Moore

- Antonio Machado

-

▼

November

(163)

Wednesday, November 17, 2021

Antonio Machado

Marianne Moore

NO SWAN SO FINE

"No water so still as the

dead fountains of Versailles." No swan,

with swart blind look askance

and gondoliering legs, so fine

as the chinz china one with fawn-

brown eyes and toothed gold

collar on to show whose bird it was.

Lodged in the Louis Fifteenth

candelabrum-tree of cockscomb-

tinted buttons, dahlias,

sea-urchins, and everlastings,

it perches on the branching foam

of polished sculptured

flowers--at ease and tall. The king is dead.

Wallace Stevensl

Tea at the Palaz of Hoon, by Wallace Stevens

The western day through what you called

The loneliest air, not less was I myself.

What was the ointment sprinkled on my beard?

What were the hymns that buzzed beside my ears?

What was the sea whose tide swept through me there?

Out of my mind the golden ointment rained,

And my ears made the blowing hymns they heard.

I was myself the compass of that sea:

I was the world in which I walked, and what I saw

Or heard or felt came not but from myself;

And there I found myself more truly and more strange.

Tuesday, November 16, 2021

W. S. Merwin

Before the Flood (1998)

Why did he promise me

that we would build ourselves

an ark all by ourselves

out in back of the house

on New York Avenue

in Union City New Jersey

to the singing of the streetcars

after the story

of Noah whom nobody

believed about the waters

that would rise over everything

when I told my father

I wanted us to build

an ark of our own there

in the back yard under

the kitchen could we do that

he told me that we could

I want to I said and will we

he promised me that we would

why did he promise that

I wanted us to start then

nobody will believe us

I said that we are building

an ark because the rains

are coming and that was true

nobody ever believed

we would build an ark there

nobody would believe

that the waters were coming

W.S. Merwin

Berryman

Monday, November 15, 2021

William Carlos Williams

St. Francis Einstein of the Daffodils

On the first visit of Professor Einstein to

the United States in the spring of 1921.

Agha Shahid Ali

Snowmen

Paul Blackburn

7th Game: 1960 Series

Nice day,

sweet October afternoon

Men walk the sun-shot avenues,

Second, Third, eyes

intent elsewhere

ears communing with transistors in shirt pockets

Bars are full, quiet,

discussion during commercials

only

Pirates lead New York 4-1, top of the 6th, 2

Yankees on base, 1 man out

What a nice day for all this !

Handsome women, even

dreamy jailbait, walk

nearly neglected :

men's eyes are blank

their thoughts are all in Pittsburgh

Last half of the 9th, the score tied 9-all,

Mazeroski leads off for the Pirates

The 2nd pitch he simply, sweetly

CRACK!

belts it clean over the left-field wall

Blocks of afternoon

acres of afternoon

Pennsylvania Turnpikes of afternoon . One

diamond stretches out in the sun

the 3rd base line

and what men come down

it

The final score, 10-9

Yanquis, come home

Paul Blackburn

Brooklyn Narcissus

Straight rye whiskey, 100 proof

you need a better friend?

Yes. Myself.

The lights

the lights

the lonely lovely fucking lights

and the bridge on a rainy Tuesday night

Blue/green double-stars the line

that is the drive and on the dark alive

gleaming river

Xmas trees of tugs scream and struggle

Midnite

Drops on the train window wobble . stream

My trouble

is

it is her fate to never learn to make

anything grow

be born or stay

Harbor beginnings and that other gleam . The train

is full of long/way/home and holding lovers whose

flesh I would exchange for mine

The rain, R.F.,

sweeps the river as the bridges sweep

Nemesis is thumping down the line

But I have premises to keep

& local stops before I sleep

& local stops before I sleep

The cree-

ping train

joggles

rocks across

I hear

the waves below lap against the piles, a pier

from which ships go

to Mexico

a sign which reads

PACE O MIO DIO

oil

“The flowers died when you went away”

Manhattan Bridge

a bridge between

we state, one life and the next, we state

is better so

is no

backwater, flows

between us is

our span our bridge our

naked eyes

open her

see

bridging whatever impossibility. . . PACE!

PACE O MIO DIO

oil

“The flowers died. . .”

Of course the did

Not that I was a green thing in the house

I was once.

No matter.

The clatter of cars over the span, the track

the spur

the rusty dead/pan ends of space

of grease

We enter the tunnel.

The dirty window gives me back my

Donald Justice

Absences

Donald Justice

On A Painting By Patient B Of The Independence State Hospital For The Insane

1

These seven houses have learned to face one another,

But not at the expected angles. Those silly brown lumps,

That are probably meant for hills and not other houses,

After ages of being themselves, though naturally slow,

Are learning to be exclusive without offending.

The arches and entrances (down to the right out of sight)

Have mastered the lesson of remaining closed.

And even the skies keep a certain understandable distance,

For these are the houses of the very rich.

2

One sees their children playing with leopards, tamed

At great cost, or perhaps it is only other children,

For none of these objects is anything more than a spot,

And perhaps there are not any children but only leopards

Playing with leopards, and perhaps there are only the spots.

And the little maids that hang from the windows like tongues,

Calling the children in, admiring the leopards,

Are the dashes a child might represent motion by means of,

Or dazzlement possibly, the brilliance of solid-gold houses.

3

The clouds resemble those empty balloons in cartoons

Which approximate silence. These clouds, if clouds they are

(And not the smoke from the seven aspiring chimneys),

The more one studies them the more it appears

They too have expressions. One might almost say

They have their habits, their wrong opinions, that their

Impassivity masks an essentially lovable foolishness,

And they will be given names by those who live under them

Not public like mountains' but private like companions'.

Mark Strand

A Piece Of The Storm

For Sharon Horvath

From the shadow of domes in the city of domes,

A snowflake, a blizzard of one, weightless, entered your room

And made its way to the arm of the chair where you, looking up

From your book, saw it the moment it landed.

That's all There was to it. No more than a solemn waking

To brevity, to the lifting and falling away of attention, swiftly,

A time between times, a flowerless funeral. No more than that

Except for the feeling that this piece of the storm,

Which turned into nothing before your eyes, would come back,

That someone years hence, sitting as you are now, might say:

"It's time. The air is ready. The sky has an opening."

Mark Strand on Donald Justice

Don's precision in esthetic matters and his courtesy in personal ones masked, I believe, a vivid inwardness—an inwardness of the sort we sense in the paintings of Edward Hopper or even further back, say, in the paintings of Piero della Francesca. It may have been a sympathy with such projections of hiddeness that moved Don late in life to try his hand at painting. I can recall many instances of his phoning me up and asking me—because I had once been an art student—questions relating to technique. He wanted his paintings to look like they were done by a painter and not a poet. He had no desire to appear amateurish, nor to have it seem as though the making of his paintings entailed a struggle. In his artistic pursuits, which, it should be mentioned, also included musical composition, he was very much a purist, but quirkily and beguilingly so. Still, the work for which he will be remembered is of course his poems whose principle beauty lies in the wistful articulation and sad acknowledgement that little or nothing survives the great drama and effort that is life. Sorry news, but conveyed always with a certain dark, inimitable charm, beautifully, unforgettably.

Joan Retallack

Elliptical Ice Terriers

Just as your blades describe an icy metaphysic of

parallel curves, I will be your personal pronoun

for the duration of this sentence. You will be my

personal pronoun for the duration of this sentence.

It’s all about remaining in motion. Exquisite poetries

and theories of everything propel flying spins,

no-hands bicycle arias on the way home. More

reciprocal alterity, more biomimicry, less blood

sausage fealty, explosions of sweetest beauty.

My child, why repeat what some poet or another

has already said—we live our lives forever taking

leave—when a custom-fitted speech act can be

yours within 24 hours. With it you can perform

rites and ceremonies, weddings, baptisms,

extreme unctions, forgiveness of sins, funerals—

visit correctional facilities, start your own church.

Joan Retallack

None Too Soon

Located in memories without precedent, fine stock of syllables

not yet squandered in pliant affirmation. Don’t be scared. The

more non-existent of the gods are the only ones counting your

blunders. Hard to forget what’s never been known for sure.

Yearning minds conjure thoughts bound to deform the

musculature of the most determined smile. The only

worthwhile thought experiment of which I’m currently aware

is to construct a logical space-time bracket in which all of us

—animal, mineral, vegetable—are sometimes dreaming.

Joan Retallack

from

A I D /I/ S A P P E A R A N C E

for Stefan Fitterman

B H J C E R T

fo fn Fmn

1. n on w mn of onnuy n uomy pon

2. of nu nvly of qunum of on qu n nl

3. lmn of onnuy plly ppn oug uon of

4. nu of lg o o yng n lug ll ly

5. l uy of nu moon wx un o o wn wn

6. o ung lp o wn ngng on ng mkng n ng

7. pp n no pl o n on n ngly w gl

F G K Q U

o n mn

1. no n w m no on ny no my pon

2. o n nvly o nm o on n nl

3. lm no onny plly pp no on o

4. no l o o yn nl ll ly

5. l y o n moon wx no own wn

6. o n l pow n n no n n mn n n

7. pp n no pl o no n n nly w l

Clark Coolidge per Ron Silliman

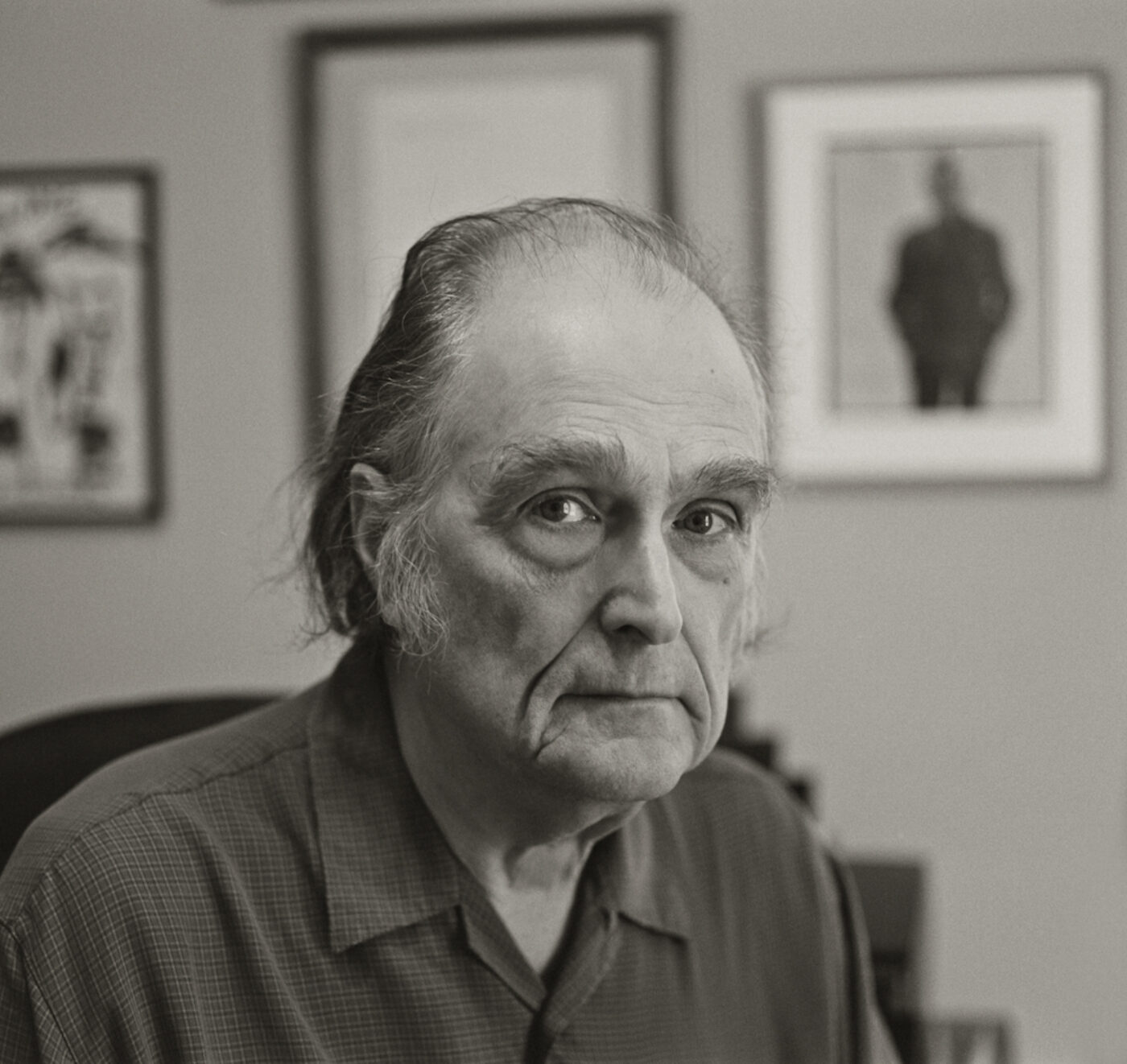

Photo of Clark Coolidge By John Sarsgard.

PMIn an interview with Tom Orange for Jacket you said, “you always have your basic language, or your subconscious choices, or whatever it is.” I’m interested in this idea of “basic language.” Does the process of retranslating compel you to bring in new language?

CCI’m basically using my memory of language—that may be one way of putting it—which would be what I remember from spoken language, and what I remember from the page. If I’m writing at a certain pace I can pick up things from all those areas and associate. I wrote a lot of these things without really realizing what I was writing. I was writing fast. I knew what the project was, of course, but I wasn’t trying to make it be something. I mean, it had to make itself something through me.

PM You’ve said that creating work can be like “feeling a shape.” Which I interpret as, finding a form and then working language into that form. Is that something you were doing with these?

CC It may have been Schoenberg who said “I sense the envelope of the piece”—I think he used the word envelope—“before I write any of the notes.” I can see, sort of dimly, this general, overall form. And then I use that. There’s some kind of—a manner of speech, I’d say—that Hanshan uses. A kind of first-person narration of memories, or events, or adventures. And I don’t think I could totally avoid that if I wanted to. It relates to the epigraph, where I talk about living on the green schist, which is the bedrock of the Taconic Range we were living on.

PM I was interested in that epigraph, partly because it gives us this geological vocabulary to run with. I know that’s very important to you. It made me think of a disagreement you once described with Aram Saroyan: his reading of your work as “a big cliff of rock.” And you said, “Geologists read the rocks.” I thought of the word schist in that context. It’s a word of differentiation.

CCIt ended up that I was a major in geology at Brown, two years before I realized, Hey, you know, you’re not going to do this. What you really want to do is run around the woods and find crystals.

PM I love thinking about these poems as the outcomes of a descriptive science of words. There’s so much careful attention paid to the properties of each word.

CC Yeah, that’s nice. As long as it carries me forward, and I’m not just stuck with some definition. Right? You wouldn’t want that.

PMLet me ask about the use of arrangement in these poems. These poems are roughly four-to-nine lines, and there’s a lot happening with enjambment. But there’s no extra space within the lines, something that you’ve worked with before.

CC By the time I was writing To The Cold Heart, I was more into phrases and sentences rather than just single words, although the single words are there. John Ashbery was interviewed, I think in the ’60s, or early ’70s, by Bill Berkson, who asked him a lot of questions about The Tennis Court Oath and that period of his writing. The main poem we were fascinated with was a numbered sequence of short poems called “Europe,” some of which are literally one word. John said, “I wanted that to be the whole experience. I wouldn’t reduce that word or associate it with anything else. I would just put it right in the middle of the page.” He said later he wanted to give that same feeling of an isolated object, a charge or whatever, to a phrase, maybe even a sentence or a paragraph. That’s something I’ve thought about, and I never associated with him, but there he is saying it in this suppressed interview that was never actually published. I guess I’m trying to say, that in terms of arrangement, I wanted to have that same emphasis on a phrase or a sentence or some longer linguistic figure. That was my argument with Aram. He would reduce everything down to one word. I would reduce it down to one word, and then accumulate other words around it.

PMThat’s an interesting way to think about the poetic phrase, a kind of accumulation.

CCBack then I wanted to put things together that didn’t normally go together syntactically. I was working with tape in the ’60s. I would put words on loops of tape. Put one word on one loop, and another word on another loop, and the loops are different lengths. Let’s say you had two words that normally go together, like “I see.” Play them at the same time and the gap between the words changes—they would be two separate words. Just two words going by each other at different speeds.

PM In the Orange interview you talk about how a project can “get ahead of you,” and compel you to “chase it down.” I think you said, “I’ve always been following something. If it stops pulling me then I will stop.”

CCThere have been times when I thought maybe I was finished. Something happened toward the end of the ’90s, just before I moved out here when I thought, You know, I’ve written an awful lot, and maybe I didn’t have to do this anymore. I mean, there’s a side of it that’s not entirely pleasant, you know? You’re pushed and pulled and you want to find what’s there. On the other hand, you get up every day and think, I’ve got to do this again? Then, within days of that feeling, I would find myself writing another line. I realized, like many of us have realized, that it’s not under our control. Evidently, this is what we’re supposed to do.

PM What are you following now?

CC Well, I’m trying to play the drums again. I had a couple of strokes a couple of years ago, and I lost function of most of my left side. My left hand and foot. I didn’t lose any speech, or brain function, but I couldn’t control my left side. I’ve gotten a lot of it back, but there still are things that aren’t automatic anymore. On the other hand, I’ve found it interesting that I’m forced to stop and look at these things that I would normally do, and think of doing other things. Maybe slower things, more simple phrases. Poetically—do you know Nathaniel Mackey’s work? Did you see that new box set that New Directions put out?

PMIt’s gorgeous.

CCThat’s almost one thousand pages of poetry. In one shot. It’s amazing. In that book there are two main poems that were happening in parallel, and he’s been writing them for twenty years. I’ve been doing something similar. I’ve realized, in the middle of all this writing, after twenty years, that it’s really all one work. I think there are about seventeen thousand pages or something like that. And I’m not exaggerating. In the last ten years it’s been mainly sonnets, which I don’t understand. I never had that much interest in sonnets, per se. I know I was really influenced by Ted Berrigan’s sonnets. A lot of us in that generation were. Even if we thought we came out of William Carlos Williams, it turned out it’s maybe so basic to the poetic effort that you can’t get away from it.

PMYou published some of your sonnets in 2013, right? With Fence Books.

.

Trying to get home, trying to get home

I pulled on the chin link until your coffin tipped.

Later, you came home. Welcome to your corner

above the books. Meanwhile I asked you to follow

me as far as I could go. You’re already farther

than that, thinning predators for history.

History being the first sign that we should

have ducked. Is changing the story the tiniest

bit really enough? Should we execute the principles,

or just the ones we wish were dead? I’ve changed

the story a little bit, though I’m not sure anyone noticed.

A little Cuban-sounding brass now from

Haitian players, mid-tempo, humid horns.

In a comment to my replies to Jonathan Mayhew’s questions the other day, Pris Campbell asked a pointed question:

After your mention of Clark Coolidge as one poet you found initially difficult to understand, I read some of his work on the Internet. This is from the beginning of The Maintains, and I hope it's okay copyright-wise to quote just the first few lines out of about a 3-4 page poem...

such like such as

of a whist

a bound

dull

the mid eft

lulu

the mode

own of own off

partly of such tin of such

the moo

which which

lably laugh

The poet Susan Howe, 77, at right, and her daughter, the painter R. H. Quaytman, 53, in Quaytman’s house, designed by the American sculpto...

-

Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) Because a razor cuts across a frame of film, I wince, squinting my eye, and because my day needs as...

-

I Wake Up Before the Machine I wake up before the machine made of all the choices we are together not making lights up this part of Oaklan...

-

The Ron Padgett Papers consist of material created and accumulated by Ron Padgett in the course of his work as a poet, translator, and e...